Huge Rejection of #Nigeria’s Unity

The week before last I posted a poll: “If #Nigeria held a referendum on national unity today, how would you vote?” The results were not great for those who believe in Nigerian unity. A whopping 80% of responses voted for a fundamental change to Nigeria. 35% want the country to break-up, and 44.6% of people voted for Nigeria to be turned into a confederation.

The vote result was a massive rejection of Nigeria’s current structure. Only 20% of people want Nigeria to continue as currently structured The fact that more than a third of people want Nigeria to end is deeply worrying.

#Nigerian Army Chief Speaks About #BokoHaram and Corruption

Nigeria’s Chief of Army Staff, Lieutenant-General Tukur Yusuf Buratai had a BBC Hardtalk interview this week with the BBC’s Stephen Sackur. Sackur gave Buratai a very serious Jerexy Paxman style grilling on varied issues such as alleged human rights issues by the Nigerian army, corruption, the Nigerian army’s ongoing fight against Boko Haram, and allegations that Buratai owns properties in Dubai.

It was quite an uncomfortable interview and it got sticky and awkward for Buaratai and several points.

What is Behind the Recent #Biafra Agitation in #Nigeria? (Part 2)

The topic that dominates Nigerian public discourse at the moment is the resuscitated demands for the secession of the eastern region as a new country called Biafra. This comes 50 years after the last (failed and very costly) attempt at Biafran secession.

Channels TV’s Kadaria Ahmed and Al-Jazeera recently hosted television shows about the new Biafra phenomenon. I was a very informative series. Please see below for the Al-Jazeera TV Show:

Zoning and Rotation: Is It Time to End #Nigeria’s ‘Gentleman’s Agreement’?

The Gentleman’s Agreement That Could Break Apart Nigeria

•

June 1, 2017

Buhari’s unwillingness to disclose the nature or extent of his illness fuels rumors that he is terminally ill or, periodically, that he has already died. Last month, Garba Shehu, a spokesman for the president, was forced to issue a series of tweets denying that anything unpleasant happened to the president. He added that reports of Buhari’s ill health are “plain lies spread by vested interests to create panic.” Buhari’s wife recently tweeted that his health is “not as bad as it’s being perceived.”

Regardless of the severity of his illness, Buhari’s extended absence risks igniting an ugly power struggle that would threaten not just the political fortunes of his ruling party but also a long observed gentleman’s agreement that has been critical to maintaining the stability of the country.

The unwritten power-sharing agreement obliges the country’s major parties to alternate the presidency between northern and southern officeholders every eight years. It was consolidated during Nigeria’s first two democratic transfers of power — in 1999 and 2007 — and it alleviated the southern secessionist pressures that had festered under decades of military rule by dictators from the north. For a time, this mechanism for alternating power helped keep the peace in a country with hundreds of different ethnic groups and more than 500 different languages. But it was never intended to be permanent, and as Buhari’s illness demonstrates, it has increasingly become a source of tension rather than consensus.

If Buhari, a northerner, doesn’t finish his term of office, and power passes to Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, a Christian from the south, it will be the second time in seven years that the north’s “turn” in the presidency has been cut short. In late 2009, then-President Umaru Yar’Adua, who like Buhari was a Muslim from the north, traveled abroad for treatment for an undisclosed illness. When Yar’Adua died in office the following year, his southern Christian vice president, Goodluck Jonathan, succeeded him, setting the stage for an acrimonious split within the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP) over whether Jonathan should merely finish out Yar’Adua’s term or run to retain the office in the 2011 election.

In the end, Jonathan ran and won in 2011. But not before 800 people were killed in riots in the north after the PDP allowed Jonathan to contest the election. The anti-Jonathan faction later resigned in protest and defected to the opposition All Progressives Congress (APC) party. Buhari led the APC to victory over the PDP in 2015.

An eerily similar scenario is now playing out in Buhari’s APC party. If Buhari dies, resigns, or is declared medically incapacitated by the cabinet, it would likely ignite a similar struggle within the APC over whether Vice President Osinbajo should permanently succeed him as president. A group of prominent northerners has already stated that Osinbajo should serve merely as an interim president and that he cannot replace Buhari on the ticket in the 2019 presidential election. Should Osinbajo succeed Buhari, win the 2019 election, and serve a full term, a Christian southerner will have been president for 18 of the 24 years since Nigeria transitioned to democracy in 1999.

There is a chance that APC leaders will convince — or force — Osinbajo to stand down in favor of another Muslim candidate from the north. But sidelining Osinbajo would pose other sectarian risks. He was chosen as Buhari’s running mate in part to counter southern accusations that the APC is a Muslim party. And although he is seen as a technocrat, Osinbajo is a powerful political force in his own right — too powerful, perhaps, to be sidelined in 2019 without alienating millions of voters. He is a pastor in the country’s largest evangelical church, which has some 6 million members, and his wife is the granddaughter of Obafemi Awolowo, one of Nigeria’s early independence politicians who is beloved in southwest Nigeria.

Yet if the north’s “turn” in power is interrupted again, it will further alienate the region — already home to the bloody Boko Haram insurgency, which has thrived in part because of government neglect — and make north-south cooperation on security, development, and a host of other critical issues more difficult. It could easily lead to another round of deadly riots, as it did in 2011. But there is a way out.

Nigeria should abandon the convention of north-south presidential power rotation now that it has outlived its purpose. At the same time, it should deepen power sharing in state and local governments, which have steadily gained influence relative to the national government since 1999. Many of the country’s 36 states and 774 local governments already practice some form of power rotation among politicians from different ethnic, religious, and geographic groups. The key will be to frame the abolition of power rotation at the presidential level as an opportunity to strengthen these norms at the state and local levels — not a chance to terminate them everywhere at once.

The reality is that most Nigerians experience government at the local level anyway. Regardless of whether Buhari or Osinbajo is in the presidential palace, state and local officials have the most purchase on the lives of ordinary citizens. Letting go of a dangerous convention at the national level while devolving more power to inclusive governance structures at the local level offers a way out of the current impasse.

#Nigeria’s Latest Ethnic Controversy

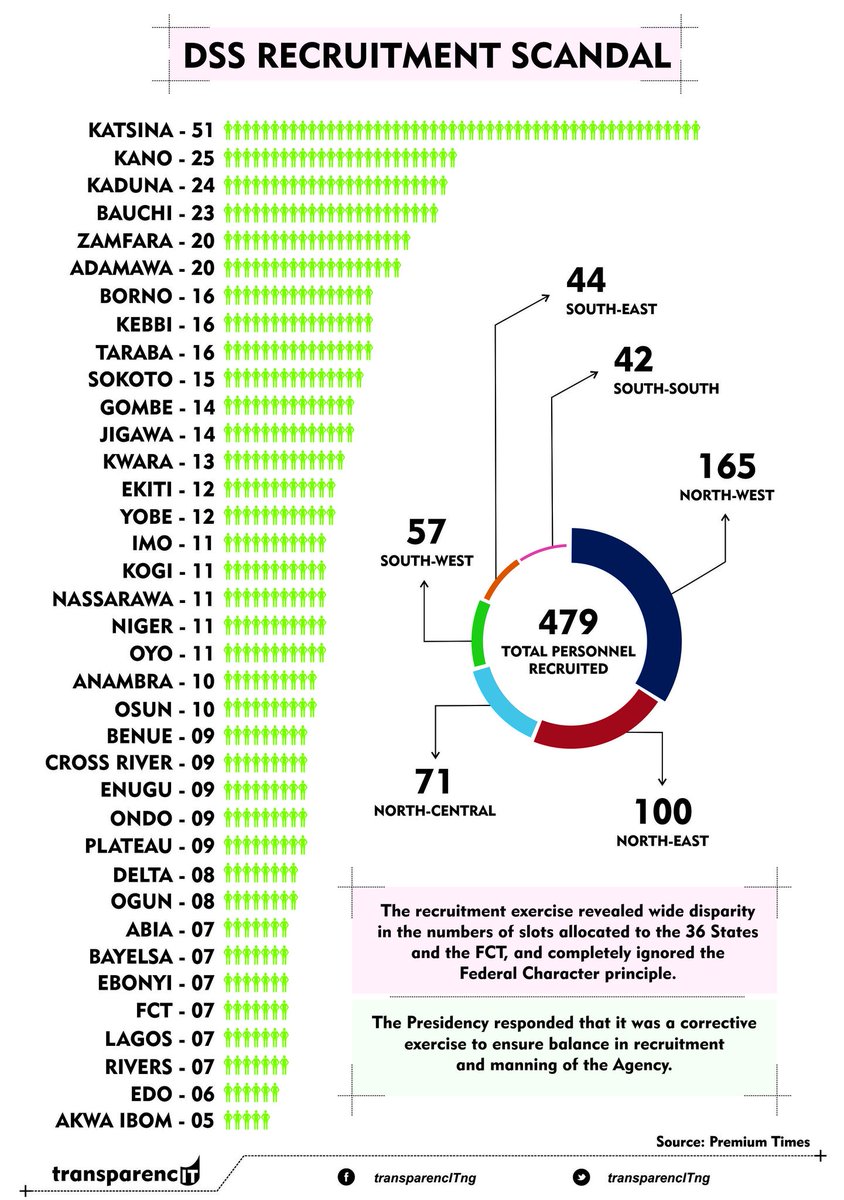

As usual in Nigeria there is a massive controversy brewing over the application of the country’s constitutional “federal character” provision for recruitment into a government agency. The State Security Service (SSS) is Nigeria’s equivalent of America’s FBI, the British MI5, or Israel’s Shin Bet.

Recruitment statistics for the latest batch of recruits into the SSS shows that new recruits from northern Nigeria overwhelmingly outnumbered those from the south. Katsina State (the home state of Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari and the the Director-General of the SSS Lawal Daura) had more recruits that any other state in the country. In a country as sensitive to allegations of nepositism, and ethnic, religious, or geographic favouritism as Nigeria, lopsided recruitment into a national agency is bound to cause trouble. Especially if recruitment shows that people from the same state as the president as the head of the SSS are being favoured.

The SSS commissioned 479 new recruits in March 2017. Of that 479 51 were from Katsina State alone, 165 are from the North-west, 100 from the North-east 100, and 71 from the North-Central zones of Nigeria. This means that over 70% of the latest SSS recruits were from northern Nigeria.

| STATE | Number of Recruits |

|---|---|

| Abia | 7 |

| Adamawa | 19 |

| Akwa Ibom | 5 |

| Anambra | 10 |

| Bauchi | 23 |

| Bayelsa | 7 |

| Benue | 9 |

| Borno | 16 |

| Cross River | 9 |

| Delta | 8 |

| Ebonyi | 7 |

| Edo | 6 |

| Ekiti | 12 |

| Enugu | 9 |

| FCT | 7 |

| Gombe | 14 |

| Imo | 11 |

| Jigawa | 14 |

| Kaduna | 24 |

| Kano | 25 |

| Katsina | 51 |

| Kebbi | 16 |

| Kogi | 11 |

| Kwara | 13 |

| Lagos | 7 |

| Nassarawa | 11 |

| Niger | 11 |

| Ogun | 8 |

| Ondo | 9 |

| Osun | 10 |

| Oyo | 11 |

| Plateau | 9 |

| Rivers | 7 |

| Sokoto | 15 |

| Taraba | 16 |

| Yobe | 12 |

| Zamfara | 20 |

Is Corruption in the #Nigerian DNA?

With corruption yet again making front page news in Nigeria, I thought it was an at time to resurrect an article I published on this website nearly 8 years ago. It asks whether corruption is a “Nigerian syndrome” and what can be done about it.

Nigeria is internationally famous for three things: oil, its Super Eagles football team, and its spectacular government corruption. However, contrary to popular belief it is quite simply a myth that corruption is perpetrated mostly by the government. Most Nigerians are paradoxically and simultaneously, accomplices, active participants, victims and agents provocateurs of corruption in their society.

LEGAL IMPEDIMENTS: Section 308 of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution

The first step to understanding corruption in Nigeria is the acknowledgment that corruption is the norm rather than the exception. Corruption is part of the system and has even been inadvertently sanctioned by the Constitution. Section 308 of the Constitution shields the President, Vice-President, Governors and Deputy Governors from civil or criminal proceedings, arrest and imprisonment during their term of office. This Section was intended to prevent frivolous lawsuits from being brought against public officers which might impede their management of their official duties. However in a country as notoriously corrupt as Nigeria, it has been a legal cloak for embezzlement, and has placed many public officers above the law. The result has been that several Governors have been able to loot state treasuries at will with no fear of arrest or prosecution.

However, corruption is not the exclusive preserve of the government. Although most Nigerians condemn corruption as a practice of the “Big Men” and government officials, most of the population are willing accomplices. There is an inherent hypocrisy among Nigerians about corruption. Most citizens acknowledge that corruption is an impediment to Nigeria’s economic development and reputation, yet the ordinary Nigerian’s unquenchable thirst for the acquisition of material wealth, possessions, fame and power fuels corruption by others.

Even those that disapprove of corruption by government officials freely admit that they would do the same if they were in government, and they simultaneously participate in practices that are inappropriate. The fuel industry is an excellent illustrative example of how corruption and dishonesty flows from the top all the way down to the lower rungs of Nigerian society. The oil industry is rightly or wrongly perceived as the epicentre of government corruption and abuse in Nigeria. Is the government alone in its abuse of the oil industry? During fuel strikes and shortages petrol stations have frequently been accused of surreptitiously hoarding fuel in order to deliberately amplify shortages and drive prices even higher. In other words they exploit and deteriorate the misery of the already hyper-extended fuel consumer.

Malpractice is not limited to petrol station proprietors. Black market street sellers of fuel in such circumstances are also distrusted by some motorists. Motorists often accuse them of diluting the petrol they sell with other chemicals. In the “food chain” of the oil industry, private citizens also dangerously “tap” oil from pipelines in order to sell on the black market. We should avoid using benign words like “tap” and call the practice what it is: theft. This theft is carried out with no remorse for the fact that the oil being stolen is a national resource, or any thought of the explosive danger caused by damage to pipelines. Thousands of lives have been lost in pipeline fires caused by “tapping”.

SOCIETAL PRESSURE

Once an individual lands a government job, (s)he will be inundated with near irresistible requests for ‘assistance’, finance, contracts and material benefits from members of his or her society. To resist such requests would be to risk being ostracised by their own kinfolk. The community expects and encourages the selective and disproportionate distribution of the “benefits” of government finances to the relatives and community of the government official.

The African extended family and patronage system ensures that a government official finds it culturally difficult to resist. If a government official condemns corruption and refuses to use government finances to enrich them self and their community, such an official would be denounced as foolish and would be derided for having nothing to show for their time in government. Negative comparisons would be drawn with other officials who (corruptly) enriched themselves, and the official would be asked why he was still living in the same one house while his colleagues in government have acquired ostentatious status symbols of their time in government such as cars and expensive houses at home and abroad. The current generation of Nigerians do not desire governments or institutions which seek to inhibit their ability to illegally acquire wealth.

Nigerians have become accustomed to the culture of corruption around them, and are very quick to condemn and dispense with governments that push the elimination of corruption as a major policy platform. The regime of Major-Generals Buhari and Idiagbon launched a severe and unprecedented anti-corruption campaign for over a year and a half between January 1984 and August 1985. They tried and imprisoned politicians that embezzled state funds. Before long, Nigerians were unhappy with the duo. Disapproval of their anti-corruption campaign was not explicit, but was subtly cotton wooled into ostensibly academic and sober critiques of their “high handed” and “repressive” nature. Nigerians celebrated when Buhari and Idiagbon were overthrown and replaced by a gap toothed armoured corps General from Minna named Ibrahim Babangida.

Babangida allowed Nigerians to see the ugly mirror reflection of their morality. He recognized many Nigerians for what they are: commodities whose loyalty and soul is on sale to the highest bidder. Many “pro democracy activists” denounced the corruption that took place under military rulers but were silenced by the financial “settlement” culture that was so pervasive under Generals Babangida and Abacha.

The current anti-corruption efforts of the EFCC and ICPC are derided for being “selective” and for not catching every corrupt individual. These unsophisticated criticisms are the moral equivalent of a bank robber objecting to his arrest by the police on the grounds that other bank robbers whom the police have not arrested are still on the loose. The author is of the opinion that most Nigerians should be grateful for this “selective” prosecution by the EFCC because if every corrupt Nigerian adult was arrested: (i) there would not be enough prisons and detention space to hold them, and (ii) a great deal of the workforce would be behind bars. Nigeria has bred something far more sinister and sophisticated than petty graft and bribery. The still unaccounted $12 billion dollar gulf war oil windfall, the Okigbo report that has never been acted upon and the absence of public outrage at these events is symbolic of the tacit acceptance of corrupt practices as “The Nigerian Way”.

Corruption in Nigeria is not just an offshoot of collapsed social and governmental institutions, nor is it the result of a hostile economic environment. The roots go much deeper and are symptomatic of the gradual but residual breakdown of Nigerian societal values and morality. It is the result of Nigerians’ failure to distinguish right from wrong, and of a nationwide refusal to condemn dishonesty. Nigerians only condemn corruption when they are not the beneficiaries of it.

A WAY FORWARD?

Western nations have lower levels of corruption not only because their law enforcement authorities are more zealous. The psyche of their citizens is different from that of the Nigerian. The UK and New Zealand are two countries with the lowest levels of official corruption in the world. The overwhelming majority of citizens in those countries reflexively obey the law as a matter of their nature and inner will. They do not have to be coerced into obedience. This is due to the attitudinal and societal rejection of corruption in these countries.

There is a moral consensus in these countries that corruption is degenerative for their society.What can be done for Nigeria? I propose two approaches that might be a god start. The first step is the elimination of the systemic procedure which inhibits measures aimed at eliminating corruption. Section 308 of the Constitution should be amended (not deleted) so that the President, Vice-President, Governors and Deputy Governors should be immune from civil, but not criminal proceedings.

The semantic difference is that such officials would be immune from being sued in vexatious civil litigation (with apologies to Gani Fawehinmi) but would not be immune from investigation, arrest or imprisonment for the commission of crimes (including those involving corrupt practices and financial impropriety). However such a constitutional amendment is unlikely to occur anytime in the near future.

The prerequisites for a constitutional amendment are formidable. Constitutional amendments in Nigeria require a two-thirds majority approval vote in the federal Senate and House of Representatives, and further approval by two-thirds of the 36 State House of Assemblies in Nigeria. To reach such a degree of consensus in a country as large and fractious as Nigeria would be near miraculous. Other methods are required. Nigeria needs a moral revolution. That moral revolution cannot be accomplished while the present generation remains. Many members of the present generation have been so utterly corrupted that they are beyond redemption. Nigeria cannot and will not progress until they expire. Hope lies in the young and unborn who have not yet been tainted by the society around them. By inculcating from a young age, the destructive social effects of corruption, a new more honest generation may emerge in future. The teaching of values should be compulsorily incorporated into academic syllabi from primary school until the completion of university. I will not deny that this sounds like a subtle form of indoctrination, but it might be the only way to save Nigeria from itself. Corruption in Nigeria will be brought down to manageable levels only when a national consensus is reached that corruption is a corrosive impediment, and when it is rejected by the majority of the population.

https://twitter.com/maxsiollun

Many #BokoHaram Members Have Never Read the Koran

Below is an article I wrote in the New York Times about the changing nature of Boko Haram’s threat and the likely next stage in the group’s evolution.

A few excerpts:

the group now seems to spend as much time engaged in banditry as it does fighting “Western education.” When officials from Nigeria’s Office of the National Security Adviser interviewed Boko Haram prisoners, they were told that most of the group’s soldiers “have never read the Quran.”

Also the group seems to be changing tactics:

Today, Boko Haram is no longer occupying large parts of Nigeria. Instead, it has morphed into a group of well-organized bandits. The military’s successes changed Boko Haram’s threat, but didn’t eliminate it.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/19/opinion/can-boko-haram-be-defeated.html?_r=0

#BokoHaram Make #Isis Look Like Playtime”

Harrowing accounts of the suffering and abuse that Boko Haram has inflicted on the young women and children it has kidnapped. Not for the faint hearted. This story is a very chilling portent for the Chibok girls. Even if they are rescued, they may not be welcomed back in their communities.

The article said that the “Chibok girls — rather than being a cause célèbre — have become bogeymen”. A Chibok resident whose cousin is among the kidnapped girls said “Even if my cousin is freed, we will be scared and can’t trust her — no one will want to marry her. I would personally be very scared of her”.

http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/public/magazine/article1680538.ece

A fight for the soul of the world

When 276 schoolgirls were abducted by Boko Haram, the world responded with the #BringBackOurGirls campaign. Two years on, 219 are still missing. Why? A five-month investigation by The Sunday Times reveals the chilling truth that shames us all. Christina Lamb reports from Nigeria

Ruqaya al Haji was only 11½ when she was captured by Boko Haram. She is now 13 and pregnant by a terrorist. She escaped in January, and is in a refugee camp (All photographs by Justin Sutcliffe)

When Boko Haram came for her, Ruqaya al Haji was only 11½ and about to start high school. Now 13, and four months pregnant by a terrorist she was forced to marry, some people from her home town call her a “mother by force”. Others call her “bad blood” or even “vampire”, and believe she has been brainwashed and trained to kill.

The gunmen who came for her left a payment. For 2000 naira (£7), she became one of three wives to a fighter called Khumoro. “I knew if I ran away there were people on the roads who would take us back and kill us,” she says. Her strange stillness inside her black-and-white shawl and the hollowness in her eyes speak of things no one should suffer, least of all a girl who is still herself a child.

When I ask what Khumoro did to her, Ruqaya looks at the ground. She says, instead of going to school, she was repeatedly raped. If she refused to submit, she was forced to watch videos of people having their throats slit and was told others would be murdered in front of her. “We were taken to watch a woman having her head broken with rocks for adultery,” she says.

Eventually, in January, she escaped, walking and running for three days to get back to her home town of Bama, in northeast Nigeria, which the Nigerian army had recently recaptured from Boko Haram. From there, she was taken 45 miles west to the Dalori camp outside the Borno state capital of Maiduguri, home to more than 20,000 refugees from Bama. There, rather than the safety she sought, she is facing a new nightmare.

Enslaved: a Boko Haram video released in May 2014 shows about 130 of the Chibok girls (Reuters)

“People believe those who were abducted [by Boko Haram] have become sympathisers with the terrorists and had a spell cast over them,” explains Dr Yagana Bukar, a lecturer at Maiduguri University who also comes from Bama, and who interviewed dozens of these women in camps across Maiduguri for a recent report by the charity International Alert and Unicef. “Because camps are organised by village, everyone knows your story and no one wants to associate with those taken by Boko Haram. So after everything else they have been through, they end up ostracised.”

The Global Terrorism Index ranks Boko Haram as the world’s deadliest terrorist group. In its ever more violent quest to create an Islamic caliphate in northern Nigeria, the group has killed more than 15,000 people, razed villages and forced more than 2m people to flee their homes over the past seven years. Living up to its name, which translates as “western education is forbidden”, it has also forced more than 1m children from school, according to Unicef, burning their buildings and abducting thousands to work as cooks, lookouts and sex slaves.

Those are the lucky ones. The refugee camps have noticeably few young men. When Boko Haram goes into a village, it often forces the teenage boys to dig trenches, which they fall into after lining up to have their throats cut. We know this because the terrorists film it. They also film schoolgirls being raped over and over again until their screams become silent Os.

“Boko Haram make Isis look like playtime,” says Dr Stephen Davis, a former canon at Coventry Cathedral who has spent several years negotiating with the terrorists. Among the horror stories he recounts is one about a man known as “the Butcher”, who is renowned for severing heads from behind in one slice.

00:0000:00Dr Ferdinand Ikwang, who runs a deradicalisation programme for former Boko Haram members and captives, tells me that among a group of women and girls released last year was a five-year-old who had been raped so many times that her pelvis had shattered and she “walks like a dog”.

The first many people around the world heard of Boko Haram was when a Twitter-savvy lawyer in the Nigerian capital, Abuja, came up with the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls, after 276 schoolgirls were abducted from a boarding school in the small town of Chibok while sleeping in their dormitories on April 14, 2014.

The abduction of thousands of girls — including Ruqaya and many others I met in the camps — had gone almost unreported, as had a massacre at a boys’ boarding school in Buni Yadi less than two months earlier, in which 59 boys were shot dead or had their throats slit. Indeed, what happened to the Chibok girls was so common in Nigeria that the government of the then president, Goodluck Jonathan, was painfully slow to react — and was taken aback by the international interest that followed.

A video released by Boko Haram on May 12, 2014, a month after the abduction, showed about 130 of the Chibok schoolgirls in full-length hijabs, under trees, reciting from the Koran. Although northern Nigeria is mostly Muslim, Chibok is a mixed community and many of the girls were Christian. “I abducted your girls,” cackled Boko Haram’s leader, Abubakar Shekau, grinning and stretching out his hands like an evil clown. “I will sell them in the market, by Allah. I will sell them off and marry them off.”

Within weeks, #BringBackOurGirls was Twitter’s most tweeted hashtag — it has now been retweeted more than 6.1m times — and world leaders and celebrities as diverse as David Cameron, Hillary Clinton, Naomi Campbell and Kim Kardashian were holding up placards demanding “Bring back our girls”. Cameron promised Britain “will do what we can” to return them to their families, and Michelle Obama took over her husband’s weekly presidential address on Mother’s Day to say, “In these girls, Barack and I see our own daughters,” and promised to help bring them back.

Cause celebre: superstars at the Cannes Film Festival in 2014 join the millions of people worldwide who expressed their concern (Getty)

Two years on, fine words and pledges appear to have been forgotten as the world finds itself swamped in new crises. Apart from 57 who escaped right at the start, the Chibok girls are still missing. It as if they have vanished off the face of the earth. Given the international outrage and all the high-profile campaigning, how is that possible? Davis, who spent months in northern Nigeria last year, is apoplectic. “I couldn’t believe you take 276 girls and leave no trace,” he says. “They would have had a convoy of 500 people — think how many vehicles that means — yet they didn’t even leave a single wheel track, and not one villager saw them pass. It’s totally beyond belief.”

The campaigners say the Chibok girls are likely to have been split into groups and taken to Boko Haram strongholds in the Sambisa forest, an area three times the size of Wales, or the remote Mandara mountains, which border Cameroon. Some may have been taken into neighbouring Chad or Cameroon, where Boko Haram is also active. “From various contacts we’ve had, they are not in a single location,” says Jeff Okoroafor of the Bring Back Our Girls (BBOG) campaign. “We believe some have been taken outside the country and some have been forcibly married. Many have been impregnated to create a new generation of Boko Haram.”

A spate of more than 50 female suicide bombings across northern Nigeria, which began in June 2014, two months after the abduction, has led to fears that the girls have been brainwashed and trained to be killers, or forced to become suicide bombers, their vests triggered remotely.

In a meeting with about 300 of their parents on January 14 this year, the new Nigerian president, Muhammadu Buhari, said his government had “no credible intelligence” on the girls’ whereabouts, or even whether they were still alive.

But after a five-month investigation, The Sunday Times has learnt that there have indeed been sightings: both by US surveillance and by other girls released in recent months. And as Ruqaya’s story shows, finding them might be only the start of their problems.

They started shooting boys in the head in front of us. My mum is sacrificing for me to go to school, but I have nightmares every night and I can’t concentrate

Every evening, as dusk falls over Abuja, a group of activists gathers for a sit-out at Unity Fountain, a dusty traffic island with a dried-up water feature. The day I go marks 691 days since the Chibok girls were abducted. A few passing motorists honk in solidarity at the huddle of 12 people wearing red BBOG badges. A few more drift in after work, but an untouched pile of plastic chairs shows how the numbers have fallen off from two years ago, when hundreds would meet here.

“No one is giving up,” Yusuf Abubakar, the coordinator of the sit-out, insists. He points out that the Danish foreign minister, Kristian Jensen, had visited recently and a group of British MPs are also due in a few days. “We say the fight for the return of the Chibok girls is the fight for the soul of Nigeria, but Jensen corrected us and said, ‘It’s a fight for the soul of the world,’ ” Abubakar says. “What moral right do we have to tell our children to go to school when we can’t protect them there?”

Various matters are discussed, such as refreshments for a forthcoming candlelit vigil in memory of the slain Buni Yadi boys. As always, the session ends with everyone singing John Lennon’s Give Peace a Chance, reworded to say: “All we are saying — bring back our girls/Now and alive!”

I return the next day. Ten of the Buni Yadi boys’ fathers have come on a nine-hour road trip for the vigil, all holding photographs of their dead sons. Not only did they lose their children when Boko Haram swept into their town, but also their homes. “No one talks of our plight,” says SA Dadikowa, who found the body of his son Bamaigon Ali, 16, in a pool of blood, shot in the back.

“I abducted your girls”: Abubakar Shekau, centre, the leader of Boko Haram, and his thugs have committed unspeakable horrors Standing with her mother, heads bowed as they light a candle, is a girl whose tear-streaked face is so riven with tragedy that I can hardly look at her. Now 16, Maryam, left, was in the girls’ section of Buni Yadi school the night of February 24, 2014, when Boko Haram attacked. Her elder brother, Shoaib, then 16, was in the boys’ part of the school. The girls were taken into the mosque. “They said they would let us go — but going to such a school was wrong and, if they caught us again, they wouldn’t spare us,” says Maryam. “Then they started shooting boys in the head in front of us.” Others had their throats slit and they heard the screams. She never saw her brother again.

“He wanted to be an architect,” says Maryam’s mother, Fatima. “I fainted when I heard the news.”

Fatima is paying for her daughter to go to school in Kaduna, but Maryam weeps as she tells me: “I can’t concentrate because I keep thinking of my brother and what they did to those boys. I know my mum is sacrificing for me to go to school, and I didn’t want my education to stop, but I have nightmares every night and they fill my mind.”

‘How many girls have to be raped and abducted before the West will do anything?’ says the hostage negotiator

Many of those at Unity Fountain feel let down. “The world made a lot of this, but, two years on, none of the girls is back,” complains Dr Oby Ezekwesili, the former Nigerian education minister and World Bank executive who has been a forceful presence in the campaign. “Every time a world leader gets up and says girls should go to school, they lack moral credibility when 219 brave girls went to school in a place called Chibok and never came back.”

Esther Yakubu, 42, a finance officer for Chibok local government and the mother of one of the abducted girls, feels the same way. Her daughter Dorcas would be 18 this June. She shows me a picture of her on her phone: a smiling girl in a bright turquoise long-sleeved dress (page 22). The photograph was taken the very week of her disappearance.

“You can see she loved fashion,” she says. “She’s like a little bit of my heartbeat. She always takes care of her younger siblings without being asked, cooks. She liked singing praises and had a nice voice.”

Esther’s tenses switch between past and present. “I believe she’s alive,” she says. “I used to dream of her coming back. If she’s dead, I would know.”

Ironically, because of security fears, Esther had moved Dorcas from her school in Kano to the government college near their home town only months before the attack.

The night of the abduction, April 14, 2014, they were at home in Chibok. “Around 11pm or midnight we heard gunshots. My brother-in-law said, ‘Boko Haram is coming and we must leave.’ Chibok is a rocky place, so we hid in the rocks. They started burning things — the shopping complex, schools — and were there till 4am. We could see them riding their motorbikes, but didn’t know they had gone to the school.

“Then my brother-in-law called again and asked, ‘Where’s your eldest?’ He said the school had been attacked. I didn’t believe it, but then parents started coming back and crying. I still didn’t believe it.”

She and her husband went to the school at daybreak. “We saw the classrooms burnt, ashes everywhere and everything dumped — schoolbooks and Bibles. That day, the whole community was in mourning.”

In those first days, a few girls drifted back. Some had escaped from the trucks on the way into the forest; others had managed to pull themselves out of the trucks when they got to the forest by grabbing onto branches. They told how the men had come in army uniforms so, at first, they had not realised it was a Boko Haram attack.

Some believe there was a conspiracy behind the abduction. That night, only 15 soldiers were on duty instead of the usual 100, as some had been sent elsewhere. And there were only 27 police, most of whom, Esther says, were drunk. The school had no light as the generator had run out of diesel, and the headmistress had gone away.

A sister’s grief: the brother of Maryam, 16, was shot and killed in front of her when Boko Haram attacked their school

This theory is discounted by Hadiza Ibrahim Mohammad, 28, a teacher of Islamic studies at the school and niece of the principal. “My aunt is diabetic and a week before the attack wasn’t well, so had gone to Maiduguri for treatment,” she says.

Hadiza knows exactly what Boko Haram is capable of. She moved to Chibok after it burst into the house in Maiduguri in which she was living, in December 2012, and shot her husband — a lawyer — three times. Four months pregnant and left with nothing, she got a job at the Chibok school. She says she had been nervous ever since. On the day of the attack, she felt “a sinister atmosphere” and mentioned to colleagues that “the town looks kind of sparse, not many people in the streets”, but they laughed and said: “You’re always scared.”

That evening, one of her cousins, Margaret Shetima, known as Kume, came over to dinner. Kume, 17, was studying at the school and returned there after the meal. She and another cousin, Hauwa Maina, as well as a neighbour’s daughter, Rifkatu Galang, were taken that night.

The following day, Hadiza says, “Chibok was wailing, women rolling on the ground. People were so scared that Boko Haram would come back, they took the job of vigilantes. A hunter tried to follow in the tracks of the trucks.”

It’s not hard to see where the five or six main Boko Haram camps are. I can see them on Google Earth

At first, they didn’t even know how many girls had gone. Although there were 213 studying at the school, it was being used as an exam centre and others had come to stay. When the video was released a few weeks later, Hadiza recognised girls she had been teaching since primary school.

The international attention surprised them, and gave them hope the girls would be recovered quickly. “We heard the Americans had satellites that could see even a man walking in a street in Baghdad,” says Esther. But, when no news came, they found themselves in a kind of limbo. “I can’t sleep, I can’t breathe,” Esther says. They have been offered no counselling.

Since the abduction, the governor of Borno state (in which Chibok lies) has not visited the parents. Instead, he sent the district chairman a bag of rice, 30,000 naira (about £100) and some fabric, which he said was a gift from the president.

Hadiza says that many mothers have given up hope. “It’s only the world who are making the mothers think their children are coming back,” the teacher says. “But most think they are dead.”

Dorcas, the daughter of Esther Yakubu, below, is still missing. This picture of her on her mother’s phone was taken the week she was abducted

Yet The Sunday Times has learnt that there was a confirmed sighting of the Chibok girls — but nothing was done. Dr Andrew Pocock, who was the British high commissioner in Nigeria until he retired last July, says a substantial group of girls was located early in the search.

“A couple of months after the kidnapping, fly-bys and an American ‘eye in the sky’ spotted a group of up to 80 girls in a particular spot in the Sambisa forest, around a very large tree — called locally the Tree of Life — along with evidence of vehicular movement and a large encampment. They were there for perhaps up to four weeks, and the question was what to do about them. Answer came there none.”

Despite all the BBOG fervour in London and the White House, there was no appetite from Washington or Downing Street to put troops on the ground. “What’s more,” Pocock says, “the Nigerians never asked for that.”

Even if the question had come, he says the answer would have indicated that an attack of any kind would be far too risky, not just for the rescuers but also the girls.

“A land-based attack would have been seen coming miles away and the girls killed. An air-based rescue would have required large numbers and meant a significant risk to the rescuers and even more to the girls. You might have rescued a few, but many would have been killed,” Pocock says. “My personal fear was always about the girls not in that encampment — 80 were there, but 250 were taken, so the bulk were not there. What would have happened to them?

“It’s perfectly conceivable that Shekau, the leader of Boko Haram, would have appeared on one of his videos a week later, saying, ‘Who told you that you could try and free these girls? Let me show you what I’ve done to them…’ So you were damned if you did, damned if you didn’t. They were beyond rescue, in practical terms.”

Pocock believes that finding the girls depends on defeating Boko Haram. President Buhari’s new government has stepped up operations to this end, and has launched a multinational operation with Chad, Niger and Cameroon. Before Christmas, the president announced that Boko Haram was “technically” defeated. “Our military activities are really punching on them and now they are completely degraded,” Brigadier General Rabe Abubakar, the military spokesman, claims.

Speaking in darkness, as the lights in the defence ministry were not working, he insists: “We’ve chased them out of towns and villages and they are now only in the Sambisa forest. Their main camps in Sambisa are smashed. Now they are in total disarray and move from place to place in the forest. They can no longer organise any meaningful attack, just hit-and-run on soft targets. We recently arrested the kingpins of Boko Haram, as well as the liaison between Isis and Boko Haram. We’re now trying to get information from them.”

Western security officials are sceptical of these claims and believe that more than half of Borno state is still under Boko Haram influence.

Esther Yakubu’s daughter Dorcas was abducted by Boko Haram

It is clear, however, that many abducted girls have been rescued. “In January alone, we rescued more than 1,000,” Abubakar says. But what happens to those freed becomes horribly clear on a visit to Maiduguri. There are at least 19 camps of internally displaced people (IDPs) around the city. Ironically, given what Boko Haram stands for, most are housed in schools and educational institutions, meaning no one can go to school in Maiduguri.

Dalori camp, where I met Ruqaya, the 13-year-old “mother by force”, is the largest. It accommodates about 22,000 people and is on the edge of town, amid parched earth dotted with bare baobab trees. As the oldest camp, set in a former technical college, it is said to be the best equipped and has rows of white tents, but it is still a miserable place with only one working tap. The tents are no escape from the searing 40C heat. Rations are merely rice and a monthly bar of soap — the flour, cooking oil and beans the refugees are supposed to receive are on sale in the market just down the road.

Among those who now live there is Ba Amsa, 18, who nurses a baby as she speaks. Ba Amsa has a limp as a result of childhood polio, so when Boko Haram entered Bama in September 2014, she could not run fast enough to get away. “They caught me and my sister and took us to a kind of prison of women, where they kept me for three months, giving us lessons on Islam.”

It was a place for Boko Haram fighters to pick wives. “They would tell us, ‘Men are coming to look at you,’ and told us to stand up and show our breasts, then they would pick 5 or 10 of us. More than 20 had been taken away before they came for me. You couldn’t resist, because the men were armed with guns, and if you did they took you to the bush and killed you.”

The man who picked her was someone she knew from Bama and they stayed in a house in the village. “He was under 30 and didn’t seem to know anything about religion,” she says. When asked how he treated her, she looks away. “I couldn’t resist him,” she replies. “He was armed.”

War on wheels: the Nigerian army has launched a motorcycle battalion to combat Boko Haram — and claims to have “smashed” it

When the Nigerian army recaptured Bama, Ba Amsa was pregnant. This time she managed to get away. Her son, Abuya, now four months old, was born in the camp and she was reunited with her parents. Her four siblings — three brothers, two elder and one younger, and a younger sister — are all still missing.

Ba Amsa says she is lucky because her family still supports her. But she worries about her son’s future. “This baby is a reminder of all the pain, but this child doesn’t even know of its own existence, so it has no blame,” she says. “All the bad things that happened to me are because of the dad, not him. This child is innocent.”

Less fortunate is Hawa Modo, 15, who has an 18-month-old baby. “I know what people call me,” she says, tugging on her long brown hijab. “There’s nothing I can do,” she shrugs. “It’s my destiny.”

Like Ba Amsa, she tried to flee when Bama was attacked, but was caught and taken to a Boko Haram prison for women. “There, they used to teach us Islamic knowledge morning and afternoon, asking us to join their sect and be honourably married, otherwise we’d become concubines and used for sex,” Hawa says.

She was taken to a village called Izza and made to marry a fighter called Umar. “He forced himself on me,” she says. He already had one wife, and after Hawa had been with him for 15 months, he bought another one. The only relief came when he used to go off on operations. “I thought about escaping all the time, but if they caught me they would take me into the far, far bush and kill me,” she says.

Intriguingly, she insists that she saw some of the Chibok girls. “When they attacked Bama, they brought some of the girls they were using as medical officers or nurses. One of them, called Hafsa, told us they were Chibok girls.”

That was not her only encounter with them. One day, in March last year, the Nigerian army came to Izza, so they fled to Njimiya, further into the Sambisa forest. “We ran all day and came to a village called Carimdabe. We were thirsty, so we went looking for water and went into the bush. There we saw a big tent, so we thought they would know where to find water. Inside were many girls and we didn’t understand them — they were speaking Chibok. Then the Boko Haram leader came, very angry, and said, ‘Why are you talking to them?’ and chased us away.”

The negotiator: Dr Stephen Davis, a former canon at Coventry Cathedral, with terrorists in Nigeria. He has spent months in the north trying to negotiate the girls’ release

Such sightings seem common, says Dr Yagana Bukar of Maiduguri University. “I keep meeting people who say they met Chibok girls, so it seems they are quite scattered,” she adds. Her own cousin was kept by Boko Haram in Bama for seven months and fell ill. “When Boko Haram take places, they run a kind of administration, so they took her to hospital and the young girls doing the drip told her they were Chibok girls. She asked why they didn’t escape, but they said they were constantly monitored.”

None of the girls I speak to had been trained to fight — instead, they had been sex slaves. But they had heard that girls were being trained as suicide bombers in a particular camp. I am told about about a girl in Dalori camp, thought to be 9 or 10, who had been sexually abused, and who was found in the bush. She is so traumatised that she cannot say her name. No one knows where she is from, she just keeps saying “Bomb”.

Bukar questions how the government will cope with the scale of this trauma. “When we did interviews with religious leaders, traditional leaders, village officials, every single one had wives and daughters abducted, which shows the magnitude of this,” she says. “We’re talking thousands of them.”

Even the wife of the traditional ruler of Bama is still missing, someone tells me.

The ostracising that goes on in the camps isn’t the end of the nightmare. “Sexual abuse is common here,” Bukar says. “Everyone is involved — army, camp officials. These people have barely 20 naira [7p], they don’t have food and will do anything.”

The superintendent of one camp is currently on trial for raping children.

Some women find the conditions in the camps so unbearable that they prefer to live outside, begging on the streets.

What these stories make clear is that even if the Chibok girls do come back, their communities may not welcome them.

“Bringing back the Chibok girls would amount to importing vampires into the country,” warns one woman, Hajiya Aishatu, who was taken captive by Boko Haram after her husband and two daughters were killed, and was recently freed following an army operation. “They have been trained to see this country as the land of evil men.”

Many people tell me a story that one of the Chibok girls came back and killed her sister in the night. Another is said to have come back and poisoned her family. Neither story seems to have any basis in fact, yet to many people, Chibok girls — rather than being a cause célèbre — have become bogeymen.

“The girls are stigmatised,” says the teacher Hadiza. “Even if my cousin is freed, we will be scared and can’t trust her — no one will want to marry her. I would personally be very scared of her.”

People talk of them being trained to slit throats and believe that the recent spate of female suicide bombers are Chibok girls. One attack in January killed 16 people in Chibok. The Nigerian military spokesman, Brigadier General Abubakar, confirmed that Boko Haram has been training women to kill. “In just one day last month, we rescued 163 women who they were radicalising. They were promising women, ‘If you kill someone you will go to heaven.’ ”

The Chibok girls aside, how has an organisation widely derided as a “ragtag bunch of thugs” been able to wreak such havoc in Africa’s richest and most populous country? “Money and politics,” says Dr Davis. “It’s not unusual in Nigeria for local political candidates to sponsor thugs and arm them to lean on political opponents. The problem is turning these guys off after the election.”

In particular, he points the finger at Ali Modu Sheriff, governor of Borno state from 2003 to 2011, who he says encouraged Boko Haram to get himself elected. “After the 2007 elections, he didn’t need the boys any more and stopped the money flow. But the boys were so heavily armed, they didn’t like that, and ended up staging an all-out attack in 2009.”

Ba Amsa, 18, with her son, Abuya, whose father is a Boko Haram soldier. “This child has no blame,” she says

In that attack, the group’s founder and leader, Mohammed Yusuf, was captured by the military and executed by the police. He was replaced by his deputy, Shekau, under whom the group has expanded and shifted its focus from purifying Islam to widespread killing and looting and establishing a caliphate. Last year Shekau pledged allegiance to Isis.

Sheriff is now chairman of the opposition People’s Democratic party, having switched sides before last year’s presidential elections to the losing side. The former governor tells The Sunday Times that allegations that he funded Boko Haram in its early days are ludicrous. “I have never had any dealings in my life with any members of Boko Haram. People who say that are doing it for political reasons to destroy my image and career. Yes, I was governor when they attacked Maiduguri, but when I left as governor, they had been chased out and the state was peaceful. Every one of them arrested said I was their No 1 target. If I’m anything to do with Boko Haram, why would that be?”

There is another issue. Nigeria is notorious for corruption, and western diplomats believe its military leadership saw the war against Boko Haram as a nice little fundraiser. “Put it this way,” says one. “The defence budget for 2013 and 2014 was $4bn-$5bn, but our estimate was that $600m was spent. Where did the rest go?”

On January 15, President Buhari ordered Nigeria’s anti-corruption watchdog, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, to investigate 20 retired and serving military officials over alleged arms procurement fraud between 2007 and 2015.

As always in Nigeria, the story is murky. There is corruption on all sides. “Mothers who appear as parents of Chibok girls are not the real mothers,” says Davis. Many others I meet tell me the same. But Davis saves his strongest criticism for the international community. “It was rather hard to believe that no one could find more than 200 girls,” he says. So convinced was he that the girls could not be so hard to find, he made some calls to Boko Haram commanders who had been involved in previous peace negotiations he had conducted.

“Three calls, three commanders,” Davis says. “They said, ‘Of course we know who has the girls.’ So they spoke to some of those who had them, and they said they might be prepared to release them.” So on the strength of that, Davis went to Nigeria last April and spent three months in the north, despite “standing out like a lighthouse”. He asked for proof of life. They gave him videos of the Chibok girls being raped.

Brigadier General Rabe Abubakar of the Nigerian army told Christina Lamb that Boko Haram has been training female suicide bombers

Davis learnt that 18 of the girls were seriously ill — many are also HIV positive — so he suggested taking them off their hands. Three times a deal was almost concluded. “Once it got as far as them taking some of the girls to a village for a handover, but then another group took them, sensing a money-making opportunity.

Frustrated and facing threats, Davis eventually had to leave for health reasons. He insists the location of the camps is well known and that it is impossible that US, British and French intelligence do not know where they are. “It’s not hard to see where the five or six main camps are,” he says. “I can see them on Google Earth. You tell me they can’t see these camps from satellite tracking or drones? Meanwhile Boko Haram goes unchallenged and every week sets off from those camps to slaughter and kidnap hundreds more girls and young boys. How many girls have to be raped and abducted before the West will do anything?”

The irony is that the girls’ international status has made them more valuable to the terrorists and thus harder to rescue.

“Boko Haram sees the Chibok girls as their trump card,” says a Nigerian military commander in Maiduguri. “We think they are keeping them with their main leadership. The day we get to the Chibok girls will spell the end of Boko Haram, but I fear they will kill all the girls in mass suicide bombings in the process.”

Meanwhile, Esther Yakubu and the other parents wait, desperate to see their long-lost daughters, but also fearful of what they will find. “I have nightmares about her being raped,” Esther says. “But in those nightmares, I embrace her. For me it’s not a problem if she’s been raped, pregnant, converted to Islam, I just want to see her. We just want our daughters back, no matter what the condition.”