Spoiler alert: if you want to read an article about African football featuring the archetypal video footage of barefoot African children playing on a bobbly dusty pitch, or an African player talking about his poverty stricken upbringing – stop reading now! There will be none of that here. Conversely, if you want to read an article about African football with deep analysis, revealing historical insights, and lots of information you probably do not know – then keep reading…

African players can take the blame and the credit for proving the greatest player of all time wrong, every day of the week for the past 22 years. When Pele made his now infamous prediction that an African country would win the World Cup before the year 2000, it did not seem bizarre. Yet, 22 years after 2000, not only has no African country won the World Cup, no African country has reached the quarter-finals since 2010. Even Asia has progressed further than Africa as South Korea reached the semi-final 20 years ago.

African countries have produced some of the World Cup’s most iconic moments: such as Cameroon stunning world champions Argentina on the opening day of the 1990 tournament, and Cameroon were only 7 minutes away from beating England and reaching the semi-final before two Gary Lineker penalties eliminated Cameroon.

Then came Rashidi Yekini’s spine tingling celebration after scoring Nigeria’s first ever World Cup goal in 1994:

History repeated again in 2002 when the late Papa Bouba Diop’s goal helped Senegal beat world champions France on the opening day of the 2002 tournament, before Senegal reached the quarter-final:

Ghana also emulated Cameroon and Senegal in 2010 when it also reached the quarter-final.

As a bonus I have also included a video of gratuitous violence: Benjamin Massing of Cameroon’s tackle on Argentina’s Claudio Cannigia in 1990 that resembled a gangland contract hit more than a tackle on a sports field:

Despite these presumed breakthrough moments, why have African teams not been able to transition from creating entertaining memories at the World Cup to actually winning it?

It cannot be a lack of talent. The best player in the Premier League is an African, several African players have won the Champions League, and African players currently play for the champions of England, Germany, France, Italy, and Portugal. Ironically, African football teams became less successful at the World Cup when their individual players’ profiles hit at an all time high.

Those who like simple, binary solutions should look away now! There is no single reason why no African country has won the World Cup. Instead, there are many. For ease of reference, I have grouped them into things that are the fault of African countries, and things outside their control.

Self-Sabotaging FAs

If there was a manual on how to sabotage a national football team, many African football associations would be best selling authors of it. Time and time again, African FAs have created poisonous relations with their footballers (who are accustomed to first class superstar treatment while playing for their European clubs) by getting into bonus rows with players, not arranging adequate accommodation or training facilities for players, or interfering with the coach’s job by forcing him to pick or drop players he does not want to. Although I could write an entire book about African FAs, I will spare you that and limit myself to the worst examples of corrupt incompetence by African FAs.

At the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, a row between Ghana’s football association and players over unpaid bonuses led Ghana’s layers to threaten to boycott and forfeit their final group game against Portugal. The row became so incendiary that it was resolved only when Ghana’s President John Dramani Mahama intervened and arranged for $3 million in cash to be flown by a private jet from Ghana to the players in Brazil, then delivered to them by cars under police escort just before the Portugal game. Some of the players kept $100,000 in cash in their bags in the dressing room. An embarrassing photo of Ghana player John Boye kissing a large bundle of cash after receiving his bonus payment went viral online.

The reader may wonder why a multi-millionaire professional footballer cares about what they get paid for playing for their country, and consider them as greedy. There are at least two reasons why bonus payments matter to African footballers. Firstly, bonus payments to African players often get siphoned off and shared amongst a host of hangers attached to the national team, FA, and government. Players feel cheated when others take money that was earned by them putting their bodies on the line while playing for their country. Secondly, African players are also subject to financial commitments and pressures that the average European player will never encounter. While a European star player usually uses his fortune to provide for his wife and proverbial 2.4 children, a star African player is also expected to provide for his parents, siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles, extended family, people from his hometown, and also be a philanthropist. Current and retired African footballers such as Sadio Mane, Samuel Eto’o, Didier Drogba, and Nwankwo Kanu have contributed vast sums of money to building and funding hospitals, schools, and charities in their countries.

The Coaching Turnstile

Keeping track of African national team coaches is an exercise in observing turnstile vacancies appear and disappear.

A favourite tactic of African FAs is to appoint a coach 3-4 years before the World Cup. The coach usually builds a rapport with the players, implements his tactics and pattern of play, and qualifies his team for the World Cup and Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON). Due to the AFCON’s scheduling, it usually occurs about 6 months before the World Cup. If said coach does not win the AFCON, his FA usually fires him, and appoints a new coach who then comes in and rips up the tactical blueprint and formation that the prior coach used and drilled the players in during the previous 4 years. The poor players then have to play in a new unaccustomed system, for a coach they do not know, while simultaneously dealing with the small matter of facing the best teams in the world at the World Cup. Even the much heralded Morocco team at this World Cup is playing for a coach (Walid Regragui) who was appointed 3 months before the World Cup started. Regragui managed Morocco in only 3 matches before the World Cup started.

Nigeria is a notorious example in this regard. Nigeria has qualified for the World Cup on 6 different occasions. Yet only 3 times has the coach who led the qualifying campaign also led the team to the World Cup. In 1998, 2002, and 2010, the Nigerian Football Federation (NFF) fired the coach 6 months or less before the World Cup started, and Nigeria went to the World Cup to play the likes of Argentina, Croatia, Denmark, and England with a coach who had met the players only a few times before the World Cup.

As if these prior examples were not enough, after qualifying for this year’s AFCON and reaching the final round of qualifying for this year’s World Cup, the NFF essentially sabotaged its own team by firing Nigeria’s coach who had made progress with the team during the past 5 years just before the AFCON. The outcome was ugly. Nigeria (which had reached at least the semi-final of the AFCON 14 times in 17 tournaments) crashed out of the AFCON in the 2nd round to a very average Tunisia team, and then failed to score a goal from open play in 180 minutes of football against an also average Ghana team in their World Cup qualifying play-off; culminating in Nigeria’s failure to qualify for the World Cup for only the second time in 28 years.

Most African countries have an incredible number of ethnic groups and languages, and multiple religious and other sectarian divides that make Northern Ireland, Israel v Palestine, and Celtic v Rangers seem like polite dinner parties. For example, over 800 languages (over 10% of all languages in the world) are spoken in Cameroon and Nigeria alone. Convincing the public that the national team coach selected players purely on merit, and without ethnic or religious bias; is a delicate act with massive ramifications that can affect national stability. It is much easier to employ a European coach with no local ethnic or religious loyalties (or axes to grind) in the African country he coaches, since he cannot be accused of ethnic bias. The logic is sound, but the execution is not.

Employing European coaches would be justifiable if African FAs hired the next Ferguson or Guardiola. However, for some head scratching reason they hire utterly dire journeyman D level European coaches. For example, Nigeria’s striker Victor Osimhen spent the last few years being coached at Napoli by a knowledgeable tactician like Luciano Spalletti, then showed up to national team duty to be coached by a German coach called Gernot Rohr who had never managed in a top four European league or won a trophy, and who got the Nigerian team job after winning nothing with Gabon, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

Appointing a coach without elite experience to coach a squad of European based superstars at the World Cup, is probably not going to end well.

Snakes and Ladders

None of Africa’s five best players is at this World Cup. Apart from Sadio Mane who is out injured, Mohammed Salah (Egypt), Riyad Mahrez (Algeria), Victor Osimhen (Nigeria), and Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang (Gabon) are fit, but not playing at this World Cup because their countries did not qualify. The reasons for that lie in the most gruelling and laborious World Cup qualification system in the world.

It is actually easier to qualify for the World Cup in Europe than in Africa. In Europe seeding generally keeps teams apart, and most decent countries can rack up cricket scores in qualifying games against mighty footballing giants like Andorra, Gibraltar, San Marino, Liechtenstein, and the Faroe Islands (some of whom have won only 1-2 games from the last 200 they have played). Of the 32 teams in the World Cup, about 40-60% (since the 1982 World Cup) are usually from Europe, and about 50% of teams in South America’s CONMEBOL confederation automatically qualify for the World Cup (in South America – it is almost harder not to qualify for the World Cup!).

In contrast, until the 1982 World Cup, Africa got to send only 1 or 2 teams to the World Cup. FIFA now allots only 5 World Cup places for Africa’s 55 countries. This means that 90% of African national teams cannot qualify for the World Cup.

African World Cup cut-throat snakes and ladders qualifiers are almost designed to ensure that Africa’s best teams never make it to the World Cup.

To whittle 55 countries down to 5, African football has a byzantine and exhausting three step qualification process. The first step is a two-legged knockout round. The winners from this round then advance to a group phase (of 10 groups). In Europe and South America, finishing top of a qualifying group means automatic qualification for the World Cup, whereas in Africa; it merely introduces a new way of being eliminated. Only the winners of each African qualifying group advance to the third round; which again reverts to a knockout cup format. The paucity of slots for African teams at the World Cup makes African World Cup qualifying extremely competitive and cut-throat, with zero margin for error. The knockout games render the top teams vulnerable to shocks/upsets, and ensure that the best teams do not make it to the World Cup. Rarely are the 5 African World Cup qualifiers the best 5 teams in Africa because the top African teams often get placed in the same group.

Because Africa has only 5 World Cup places, its countries end up in “Celebrity Death Match” groups against each other. The excellent and fluid Egyptian team that won the AFCOn 3 times in a row between 2006 and 2010 were grouped with their fierce rivals Algeria in the qualification campaign for the 2010 World Cup. In the final group qualification match, Egypt had to beat group leaders Algeria by at least two goals in a north African knockout derby. Those who are interested can read here for the background to the Egypt-Algeria rivalry.

The game was played in in front of a frenzied crowd of 100,000 and was so tense that the governments of both countries threatened diplomatic action against each other. Egypt won after scoring a 95th minute goal that sparked a pitch invasion.

Yet, that victory was still not enough for Egypt to qualify for the World Cup. Egypts win left them tied with Algeria on points, goal difference, and head-to-head results! The two teams therefore had to play a third tie-breaker play-off game on neutral territory (in Sudan!). Algeria caused an upset when they beat Egypt – meaning that perhaps the best African team of this century never played at the World Cup.

One of the qualifying groups for the last World Cup had Algeria, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Zambia. That group consisted of 4 of the last 5 African champions and the highest ranked African country at the time. A European equivalent would be Spain, France, Portugal, and Belgium in the same World Cup qualifying group from which only one of them could qualify!

Due to such blood and thunder qualifying campaigns, most African teams are usually emotionally and physically exhausted by the time they arrive at the World Cup after a gruelling qualifying campaign and playing the AFCON only 6 months before the World Cup. It is because of cut-throat qualifying incidents like this that African countries are begging FIFA for more World Cup spots.

The “Europeanisation” of African Football

20-30 years ago, most African international footballers either played for clubs based in Africa, and those who played for European clubs had first built their club careers in Africa before making a name for themselves and being signed by an African club. These days, it is rare to find an African footballer at the World Cup who has played a full season of football in an African league. Most African footballers playing in Europe go straight from African youth academies as young boys or teenagers to European clubs, and do not bother playing professional club football in Africa. Examples of players who travelled this African academy to Europe road include Thomas Partey of Ghana and Arsenal and Wilfried Ndidi of Nigeria and Leicester City.

African academies do not exist to produce players for their national team or domestic league. Instead they exist purely as factories for producing assembly line clone African players suitable for European football teams.

Many other African players were born and raised in Europe and have never lived in the African country they play for. For example, Kalidou Koulibaly and Pierre-Emerick Aubemeyang were born and raised in France and played for France at under-21 or under-20 level before opting to play for Senegal and Gabon. Hakim Ziyech was born in Holland and played for Holland’s under-19, under-20, and under-21 teams before representing Morocco at full adult international level. Many dual-national African players often opt to play for an African country only after it becomes apparent that they will not be first choice for the European country in which they were born.

This “Europeanisation” of African football means that most African players now come in two models: those trained in African academies to be a good fit for a European club, and those who grew up in Europe that European coaches have pre-drilled to play to a tactical European style (a good example is how Mourinho drilled a teenage Mikel who was a playmaking number 10, to instead become a defensive midfield destroyer). Nowadays most African teams are “Diet Europe”. Instead of playing with their own style, African countries come to the World Cup African and try to “out-Europe” the European teams with identical playing styles.

Groups of Death

Some challenges that African countries experience are not of their making. One of these is FIFA’s ranking and seeding system. Because African countries are ranked lower than their European and South American counterparts, they are always unseeded and are placed in pot 3 or 4 for the World Cup draw; inevitably meaning that African teams get drawn in a “Group of Death” with two “superpower” teams from Europe and South America. Hence Ivory Coast’s excellent Drogba-Toure et al team got put in horrible groups with Argentina, Holland, and Serbia (2006) and Brazil and Portugal (2010), while Nigeria has been placed in the same group as Argentina in 5 of the 6 World Cups that Nigeria has played in. The African hard luck story got even more bizarre at the 2018 World Cup after Senegal lost only one game and finished level on points and goal difference with Japan. However, Senegal was eliminated because its players had picked up 1 more yellow card than Japan during the tournament (yellow cards which were actually harshly awarded against Senegal’s players while playing Japan). Senegal was the first team in the 92 year history of the World Cup to be eliminated in such a manner.

Prior to the 1998 World Cup, Tunisia may have considered themselves the unluckiest team in the world. Their best defender (Abdennour) and star attacker (Msakni) got injured before the World Cup and missed the tournament. Then their goalkeeper joined them on the injured list, and the reserve goalkeeper got injured 15 minutes into Tunisia’s first World Cup game and was also ruled out of the tournament. Then in Tunisia’s second game two of their players were seriously injured and stretchered off in the first half.

The Man In Black

In addition to being in Groups of Death, African countries have also been on the receiving end of some absolutely appalling and baffling refereeing decisions. While English football fans are still apoplectic about Maradona’s handball goal against England in 1986 (36 years ago – before most of them were born!), African countries have a catalogue of refereeing grievances that the officials should hang their heads in shame for.

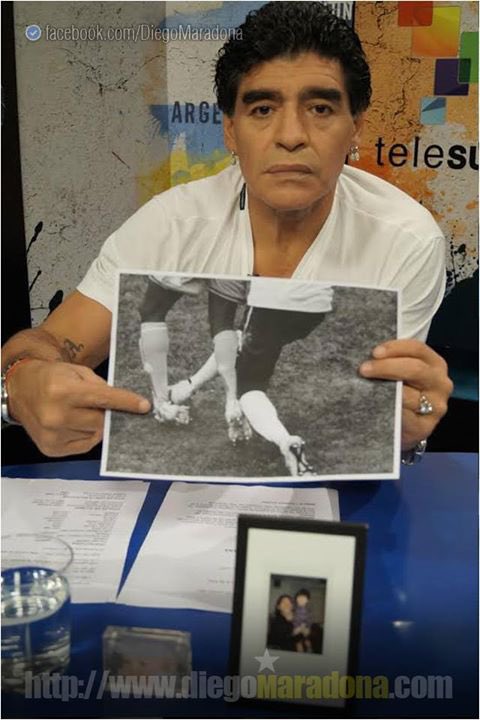

“a criminal act. It’s even worse than what Suarez did”

Nigeria played France in round 2 of the 2014 World Cup. The score was 0-0 in the second half and Nigeria’s midfielder Eddy Onazi was running the show until France’s Blaise Matuidi pole-axed Onazi with this shocking studs up, horror ankle breaker “tackle” that led to Onazi being stretchered off and put in plaster cast. For some unknown reason the American referee Mark Geiger (who was standing 2 yards away) did not send off Matuidi.

Diego Maradona (who has no axe to grind in a match between France and Nigeria) was so outraged by Matuidi’s assault on Onazi that he appeared in public with a photo of Matuidi’s studs stamping down on Onazi’s ankle and said “It is impossible that the referee did not see this challenge as a criminal act. It’s even worse than what Suarez did (biting Chiellini).”

The game completely changed after Onazi was stretchered off and France (with Matuidi who should not have been on the pitch) scored 2 late goals to win the game.

“VAR is Bull—it!” – Spain v Morocco (2018 World Cup)

The refereeing (if organised incompetence can be called that) in the Morocco v Spain game at the last World Cup in 2018 was the closest thing to match fixing I have ever seen on live TV.

Apart from the host of errors in the video above, the tragi-comic officiating culminated in the 92nd minute with Morocco winning 2-1. The ball went out of play for a Moroccan goal kick deep into injury time at the end of the game. The referee incorrectly gave Spain a corner. With the referee pointing to the left corner, and the Moroccan players facing the way he was pointing, Spain then took a quick corner from the opposite side of the pitch to where the ball went out of play, and scored a 92nd minute equaliser from it. The linesman disallowed it for offside, but VAR overruled him, and incredibly, the referee and VAR allowed Spain’s goal to stand despite the plethora of errors and rule breaking that preceded it.

It was so farcical that it provoked Nordin Amrabat (the older brother of Sofyan Amrabat who is in the current Morocco team) into his now infamous “VAR is bull—-!” comment into a TV camera after the game (which became a meme).

This was part 1 of this. In the 2nd part I will examine what African countries can do to optimise their chances of winning the World Cup.

Couldn’t argue with this write up.

[…] is the 2nd part of an article I posted a few days ago. In the first part, I examined why no African team has ever won the World Cup. In this second part, […]

[…] series of articles I am writing about why an African team has never won the World Cup. You can read Part 1 and Part 2 at these links. I concluded Part 2 with alarming stats about the number of late goals […]